Adiabatic

Adiabatic refers to a process in which no heat is transferred into or out of a system, and the change in internal energy is only done by work. Most processes in thermodynamics are diabatic which means they transfer heat. The 'a' at the start of the word adiabatic means without, so 'adiabatic' means 'no heat transfer'. Often adiabatic processes are accomplished in an insulated container, where the process happens too quickly for heat to be transferred. Since heat moves because of a difference in temperature between a system and its surroundings, an adiabatic process can also happen when the system is in thermal equilibrium.[1] The first law of thermodynamics can be expressed mathematically as:

And because the heat () is zero, the expression simplifies to:

where:

- is the change in the system's internal energy and

- is the work done on the system (if the system does work to its surroundings, the work is negative and the systems internal energy and temperature both decreases).

For an adiabatic compression (decreasing the volume of the system, like a piston), the temperature must increase. Likewise, for an expansion (increasing volume), the temperature must decrease. This is because there is no heat able to flow in or out in order to balance the temperature, which is what occurs in an isothermal process.

Variation in the Ideal Gas Law

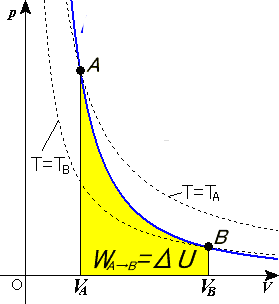

Isotherms and adiabats may look similar at first glance, but in Figure 1, it's clear that adiabats exhibit much steeper curves. Therefore, the ideal gas law slightly differs too, as seen in the equation below: [2]

where:

- is pressure

- is volume

- is gamma, which represents the specific heat ratio defined as:

- 1.67 for a monatomic gas

- 1.40 for a diatomic gas

The gas law above equals a constant, and it does so because the changes in temperature can be encompassed in this formula by measuring the changes in pressure and volume. Mathematically, integration was done to solve for this formula—and a constant is always added to the equation being integrated—resulting in the constant seen in the equation.

To get a detailed derivation of the modified ideal gas law click here.

Application

Adiabatic processes are used in the Otto cycle (when the piston does work on the gasoline) and Brayton cycles within gas turbines. Diesel engines also make use of a (somewhat) adiabatic compression in order to ignite its fuel. Adiabats are also important for the derivation of the Carnot efficiency (the maximum thermal efficiency of any thermodynamic system) which relies on two adiabatic processes.[3]

The video below (from Educational Innovations, Inc.) demonstrates an adiabatic compression: the temperature inside the chamber is increased enough to ignite the cotton.

For Further Reading

To learn more or explore one of the pages below:

- Isothermal

- Isobar (pressure)

- Isochore (volume)

- Ideal gas law

- First law of thermodynamics

- Or explore a random page

References

- ↑ H. Gould and J. Tobochnik, "Quasistatic Adiabatic Processes," in Statistical and Thermal Physics, 1st ed., Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010, ch.2, sec.11, pp. 51-55

- ↑ [2]R. Knight, Physics for scientists and engineers, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Pearson Addison Wesley, 2008, p. 527.

- ↑ R. D. Knight, "The Limits of Efficiency" in Physics for Scientists and Engineers: A Strategic Approach, 3nd ed. San Francisco, U.S.A.: Pearson Addison-Wesley, 2008, ch.19, sec.5, pp. 540-542