Mercury (pollutant)

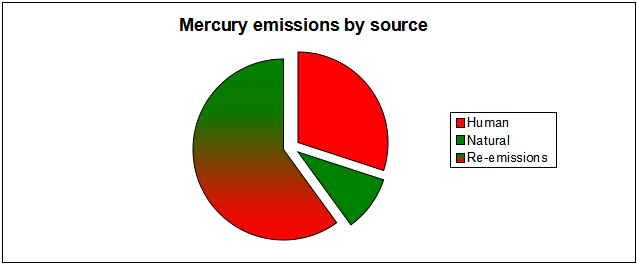

When the energy sector releases mercury (Hg) as a pollutant, it creates environmental problems. Both humans and natural sources release mercury; burning coal specifically releases quite a bit of mercury. Human activity contribute anywhere from 50-90% of the mercury present in the environment.[2][3]

The estimates are not more precise because it is difficult to figure out how much re-emitted mercury was initially emitted by humans. Re-emission occurs when previously stored mercury is reintroduced into the environment by forest fires or other means, and requires complex modelling techniques to determine how much can be traced back to human emissions.[2]

Emissions

Mercury levels in the upper layers of oceans are much higher than they were in the past, at approximately double what they were in the pre-industrial era. This is caused primarily by human emissions, which rise into the atmosphere and fall out into soils and bodies of water.[2]

Mercury is released naturally from rocks, soil, volcanoes, and by vaporization from the ocean.[3] This contributes to about 10% of the global input of mercury into the atmosphere.

In addition to coal burning, humans emit mercury with mining and smelting, cement production, oil refining, gold mining, and wastes from consumer products. Asia contributes to about half of the total human input of mercury because of the extensive coal burning for electricity.[2]

The largest emission source contributor for mercury is re-emission. This means that mercury that was previously deposited from the air onto soils, surface waters, and vegetation from past emissions can be emitted back into the air via forest fires or biomass burning. Mercury may be deposited and re-emitted many times as it cycles throughout the environment, potentially cycling indefinitely.[2]

Re-emitted mercury should not be considered natural in origin, even though it may have originally come from a natural source. As humans have introduced more mercury into the environment, re-emissions of mercury have also increased due to environmental burdens caused by the higher levels of input.[2] Continuing to add to the mercury levels will result in ever increasing levels of re-emission, and even when human emissions are cut out completely, this mercury could remain in the system for a long time. This is why it is important that continued efforts are made to reduce mercury pollution.

Mercury emissions have decreased drastically in recent years (click here and select "Mercury"), however small amounts of mercury can still be considered toxic in foods. There are limits placed on how much methylmercury can be contained within food before it is contaminated. For example, the limit for young children in Canada is 0.2 micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day.[4] So if a child that weighs 20 kilograms ingests just 4 micrograms (an extremely small amount) in a day, they would be considered to have exceeded the maximum dose. An analogy: if a 1 gram paperclip were made entirely of methylmercury and you cut it into 250 000 pieces, only one of these pieces would be required for this toxic dose!

Composition

Mercury itself is an element, just like lead or arsenic, and is classified as a heavy metal. It has many interesting characteristics (which can be read about here), some of which make it a very dangerous pollutant. In the atmosphere, elemental mercury can either converted into more toxic inorganic compounds in which oxidized mercury (Hg2+) combines with other elements, or it can combine with carbon to form a worse contaminant known as methylmercury (CH3Hg).[3] These compounds may fall onto land or water through precipitation, or they may fall as dry particles and find their way into a lake or ocean.

Effects

Humans are exposed to mercury in 2 ways:[3]

- Eating fish contaminated with organic methylmercury.

- Inhaling elemental mercury (Hg) or inorganic salts (Hg2+)

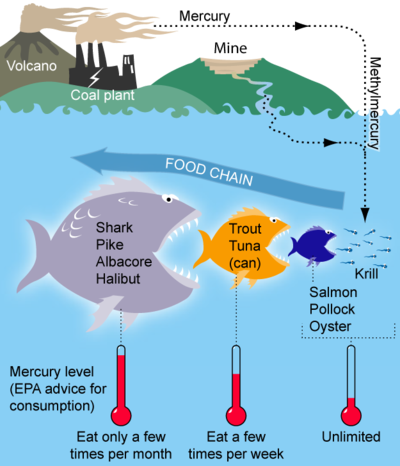

The first is the largest contributor to human effects. Methylmercury is toxic and can cause extremely adverse effects when consumed, which can happen when humans eat highly contaminated fish. Through the process of biomagnification (see Figure 1) the concentration of methylmercury within fishes increases as one goes higher in the food chain. This makes it dangerous to consume top and apex predators such as those listed in Figure 1, and especially dangerous for pregnant women and young children to do so.[3]

Effects of methylmercury can result in complex neurological problems, especially in young children and babies, by affecting the brain and nervous system. Potential issues include: cerebral palsy, delayed onset of walking or talking, learning disabilities, tremors, irritability, impaired coordination and memory loss.[3] Pregnant mothers especially should not eat larger fish as their baby is vulnerable to these chemicals that attack developing organs.

Mercury consumption can be lethal. The largest first case of this was seen in Japan in 1956 in which thousands of people were killed. Mercury dumped from a chemical plant bioaccumulated in the fish and thousands of people were in turn affected by eating them.[4]

Data Visualization

The following data visualizations show the sources emitting mercury in Canada. The "Other" category contains all sources that are non-energy related; for a more in-depth look at mercury data, including a graph showing how mercury emissions have changed over time, click here.

For Further Reading

References

- ↑ Wikimedia Commons [Online], Available: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c5/MercuryFoodChain-01.png

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 United Nations Environment Programme. 2013. Global Mercury Assessment [Online] (Accessed July 22, 2015). Available: http://www.unep.org/PDF/PressReleases/GlobalMercuryAssessment2013.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 G. Tyler Miller, Jr. and D. Hackett, "What is the threat from Mercury?," in Living in the Environment, 2nd ed. USA: Nelson, 2011, ch.24, sec.8, pp.589-590

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pollution Probe. 2003. Mercury in the Environment.