Monopsony

A monopsony represents a situation where a market has only one buyer. This lone buyer is able to reduce the price of a good or service due to the lack of competition. Similar to a monopoly, a monopsony can affect the price of a specific good or service in a market but unlike a monopoly the monopsony affects price from the demand side or buyers side of the market.[1] With only one buyer, the seller loses its bargaining power because there is no other buyer that is willing to pay a higher price for the good or service it is selling. There are two main ways which a monopsony forms, one is through mergers where by firms agree to combine themselves into one large firm and in doing so they reduce the overall number of buyers in the market. The other way is through collusion, known as an oligopsony, where firms agree on a common course of action in the market; essentially they agree not to compete which normally would result in higher prices.[2]

Imagine you are the only person in a town and there is one store; because you are the only buyer in the store, the prices of the items in the store have to reflect your willingness to pay for them. If you want a loaf of bread but only want to pay $1.00 for it, the store will have to sell it to you for that price (assuming they at least break even). Now if another person comes into town and is willing to pay $2.00 for the same loaf of bread the store will be able to raise the price to reflect the new competition for the bread.

If both people who want to buy bread work together as one entity, then there is once again the one buyer in the market; this is a merger. If you and the other person agree to only pay $1.50 for a loaf of bread then the competition has been lost and the store has to meet this price point, this is an example of an oligopsony created through collusion.

In short, the monopsony takes the competition out of the buyer side of the market in and makes the prices lower. While this sounds nice for the buyer, this lower price is clearly bad for the sellers. This can in turn put other indirect pressures can be put on the sellers, like changing the way the sellers produce goods.

Monopsony Market

When there is perfect competition in a market and the seller can sell to a number of buyers, the competition between the buyers results in an equilibrium price that is acceptable to both buyer and seller. In a monopsony market the seller can only sell to one firm so it must accept the price that the firm is offering to buy at as there is no alternative.

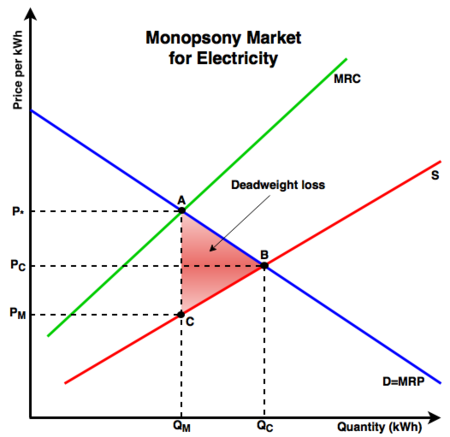

Figure 1 shows the effect that a monopsony has on a market and the comparison with a perfectly competitive market:

- At Point B the market is at equilibrium, it is competitive and the supply (S) meets the demand (D). Both the price (PC) and the quantity (QC) reflect this equilibrium.

- At Point C there is a monopsony market with only one buyer.

- In a competitive market, the change should result in the price being P* and the quantity being QM but because there is only one buyer the market ends up at Point C.

- At Point C the buyer gets the same quantity (QM) as Point A would but it only pays a fraction of the price, PM instead of P*.

- The Red Triangle (ABC) represents the deadweight loss in the market caused by the monopsony. The loss of competition results in an inefficient market. Large deadweight loss in a market can lead to market failure.

Natural Monopsony?

Not all monopsonies are bad, like natural monopolies a monopsony can be an efficient solution for a market such as the electricity market which benefits from one or a small number of large firms controlling the market.

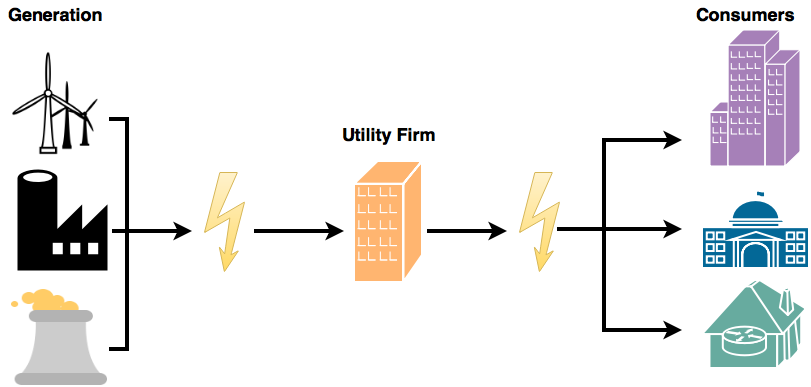

In Figure 2 there is a single utility provider for a municipal power grid. The various electrical generation firms sell their electricity to the utility firm at a low price, due the monopsonistic market. The firm sells its electricity to the grid at low prices for consumers to use. The prices are kept low due to the regulation of the utility firm and electricity market as a whole. The government decides on a certain range at which the firm can sell its electricity, by keeping the prices artificially low the government guarantees electricity for everyone at a lost cost.[3] In a market like the electricity market the existence of monopolies and monopsonies is an efficient solution due to the importance that electricity plays in today’s society.

Efficiency Trade-off

Due to the deadweight loss that a monopsony creates in the market by its nature it is not "economically efficient" but it is nominally efficient. Nominally efficient means that while in theory there could be an efficient market without a monopsony the nature of the good (i.e. electricity) needs to be protected from a certain amount of market forces in order to ensure the steady supply and price. When instituting a monopsony the society is willing to forego a certain amount of efficiency to guarantee a certain level of utility or satisfaction from electricity or like services.

We forego some market efficiency to maximize the social welfare that public goods like electricity provide. This is a perpetual debate between free market economics and mixed market economics, the goal of which is to decide whether to maximize efficiency which can lead to inequality or to maximize social welfare which seeks to minimize inequalities.[4]

There are some criticisms of the low competition market model as an efficient outcome, see monopoly.

See Also

- Monopoly

- Oligopoly

- Oligopsony

- Pareto efficiency

- Market failure

- Economies of scale

- Anti-trust legislation

References

- ↑ R.D. Blair and J.L. Harrison. Monopsony in Law and Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 1-2.

- ↑ R.D. Blair and J.L. Harrison. Monopsony in Law and Economics. pp. 12

- ↑ C. Decker. Modern Economic Regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 19.

- ↑ E.J. Mishan. Economic Efficiency and Social Welfare: Selected Essays on Fundamental Aspects of the Economic Theory of Social Welfare. Milton Park: Routledge, 1981, pp. 3.