Phase change

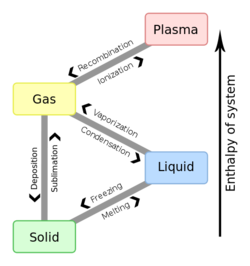

A phase change is a change from one state of matter to another in a thermodynamic system, see figure 1. These changes occur when sufficient energy is supplied to the system (or a sufficient amount is lost), and also occur when the pressure on the system is changed. The temperatures and pressures under which these changes happen differ depending on the chemical and physical properties of the system. The energy associated with these transitions is called enthalpy.

Water is a substance that has many interesting properties that influence its phase changes. Most people learn from an early age that water melts from ice to liquid at 0°C, and boils from a liquid to a gas at 100°C; but this isn't true in all circumstances. The pressure affects these transition points, so for water, the boiling point actually decreases as the pressure decreases. Water also has certain intermolecular forces which govern the temperatures at which these transitions occur.[2] This difference in boiling point is why the directions for cooking at high altitudes are sometimes slightly different (like boiling pasta longer).

The relatively large amount of energy needed to change the phase of water is one of the reasons why water is used to cool power plants. It's also part of why humans sweat in order to stay cool (through evaporation) and dogs pant. This high enthalpy also makes water important for moderating the climate.

Boiling and condensing are common phase changes as are freezing and melting. These pairs of phase changes are the most commonly experienced on Earth, but there are other phase changes, like going straight from solid to gaseous. Figure 1 also shows other phase changes, which also includes the rare (on Earth, at least) state of plasma but figure 1 does not show what happens when gases or liquids get to sufficiently high pressures and temperatures that they can't be distinguished. This phase is called the supercritical fluid state (which is useful for some modern power plants).

Visit UC Davis' Chem wiki for more information on phase changes and other chemical phenomena.

References

- ↑ Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain], Available: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APhase_change_-_en.svg

- ↑ UC Davis Chem Wiki [Online] Available: http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Physical_Properties_of_Matter/Atomic_and_Molecular_Properties/Intermolecular_Forces/Van_der_Waals_Forces