Thermal efficiency: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (1 revision imported) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Done 2018-05-18]] | |||

[[Category:Done | |||

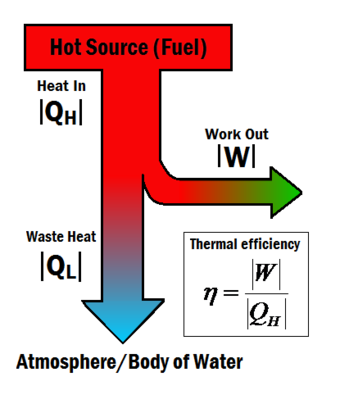

[[File:Flow Chart thing.png|340px|thumbnail|Figure 1: The amount of work output for a given amount of heat gives a system its thermal efficiency.<ref>This picture was made by the Energy Education team.</ref>]] | [[File:Flow Chart thing.png|340px|thumbnail|Figure 1: The amount of work output for a given amount of heat gives a system its thermal efficiency.<ref>This picture was made by the Energy Education team.</ref>]] | ||

<onlyinclude>The '''thermal efficiency''' of | <onlyinclude>[[Heat engine]]s turn [[heat]] into [[work]]. The '''thermal efficiency''' expresses the fraction of heat that becomes useful work.</onlyinclude> The thermal efficiency is represented by the symbol <math>\eta</math>, and can be calculated using the equation: | ||

<center>< | <center><math>\eta=\frac{W}{Q_H}</math></center> | ||

Where: | Where: | ||

< | <math>W</math> is the useful work and | ||

< | <math>Q_H</math> is the total heat energy input from the hot source.</onlyinclude><ref>TPUB Engine Mechanics. (April 4, 2015). ''Thermal Efficiency'' [Online]. Available: http://enginemechanics.tpub.com/14075/css/14075_141.htm</ref> | ||

Heat engines often operate at around 30% to 50% efficiency, due to practical limitations. It is impossible for heat engines to achieve 100% thermal efficiency (< | Heat engines often operate at around 30% to 50% efficiency, due to practical limitations. It is impossible for heat engines to achieve 100% thermal efficiency (<math>\eta = 1</math>) according to the [[Second law of thermodynamics]]. This is impossible because some [[waste heat]] is always produced produced in a heat engine, shown in Figure 1 by the <math>Q_L</math> term. Although complete efficiency in a heat engine is impossible, there are many ways to [[Waste heat#Harnessing waste heat|increase a system's overall efficiency]]. | ||

===An Example=== | ===An Example=== | ||

If 200 [[joule]]s of [[thermal energy]] as heat is input (< | If 200 [[joule]]s of [[thermal energy]] as heat is input (<math>Q_H</math>), and the engine does 80 J of work (<math>W</math>), then the efficiency is 80J/200J, which is 40% efficient. | ||

This same result can be gained by measuring the waste heat of the engine. For example, if 200 J is put into the engine, and observe 120 J of waste heat, then 80 J of work must have been done, giving 40% efficiency. | This same result can be gained by measuring the waste heat of the engine. For example, if 200 J is put into the engine, and observe 120 J of waste heat, then 80 J of work must have been done, giving 40% efficiency. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 22: | ||

There is a maximum attainable efficiency of a heat engine which was derived by physicist Sadi Carnot. Following laws of [[thermodynamics]] the equation for this turns out to be | There is a maximum attainable efficiency of a heat engine which was derived by physicist Sadi Carnot. Following laws of [[thermodynamics]] the equation for this turns out to be | ||

<center>< | <center><math>\eta_{max}=1 - \frac{T_L}{T_H}</math></center> | ||

Where | Where | ||

< | <math>T_L</math> is the [[temperature]] of the cold 'sink' | ||

and | and | ||

< | <math>T_H</math> is the temperature of the heat reservoir. | ||

'' | This describes the efficiency of an idealized engine, which in reality is impossible to achieve.<ref>Hyperphysics, ''Carnot Cycle'' [Online], Available: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/thermo/carnot.html</ref> From this equation, the lower the sink temperature <math>T_L</math> or the higher the source temperature <math>T_H</math>, the more work is available from the heat engine. The [[energy]] for work comes from a decrease in the total energy of the [[fluid]] used in the [[system]]. Therefore the greater the temperature change, the greater this decrease in the fluid and thus the greater energy available to do work is.<ref>R. A. Hinrichs and M. Kleinbach, "Heat and Work," in ''Energy: Its Use and the Environment'', 4th ed. Toronto, Ont. Canada: Thomson Brooks/Cole, 2006, ch.4, sec.E, pp.115</ref> | ||

== For Further Reading == | |||

For further information please see the related pages below: | |||

*[[Heat engine]] | |||

*[[Hydrocarbon combustion]] is often the source of heat for these engines. | |||

*[[Solar thermal power plant]] | |||

*[[Nuclear power plant]] | |||

*For thermal efficiency of car engines, click [[fuel efficiency|here]] | |||

* Or explore a [[Special:Random| random page!]] | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

[[Category:Uploaded]] | [[Category:Uploaded]] | ||

[[category:371 topics]] | |||

[[category:301 topics]] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:53, 18 May 2018

Heat engines turn heat into work. The thermal efficiency expresses the fraction of heat that becomes useful work. The thermal efficiency is represented by the symbol , and can be calculated using the equation:

Where:

is the useful work and

is the total heat energy input from the hot source.[2]

Heat engines often operate at around 30% to 50% efficiency, due to practical limitations. It is impossible for heat engines to achieve 100% thermal efficiency () according to the Second law of thermodynamics. This is impossible because some waste heat is always produced produced in a heat engine, shown in Figure 1 by the term. Although complete efficiency in a heat engine is impossible, there are many ways to increase a system's overall efficiency.

An Example

If 200 joules of thermal energy as heat is input (), and the engine does 80 J of work (), then the efficiency is 80J/200J, which is 40% efficient.

This same result can be gained by measuring the waste heat of the engine. For example, if 200 J is put into the engine, and observe 120 J of waste heat, then 80 J of work must have been done, giving 40% efficiency.

Carnot Efficiency

There is a maximum attainable efficiency of a heat engine which was derived by physicist Sadi Carnot. Following laws of thermodynamics the equation for this turns out to be

Where

is the temperature of the cold 'sink' and

is the temperature of the heat reservoir.

This describes the efficiency of an idealized engine, which in reality is impossible to achieve.[3] From this equation, the lower the sink temperature or the higher the source temperature , the more work is available from the heat engine. The energy for work comes from a decrease in the total energy of the fluid used in the system. Therefore the greater the temperature change, the greater this decrease in the fluid and thus the greater energy available to do work is.[4]

For Further Reading

For further information please see the related pages below:

- Heat engine

- Hydrocarbon combustion is often the source of heat for these engines.

- Solar thermal power plant

- Nuclear power plant

- For thermal efficiency of car engines, click here

- Or explore a random page!

References

- ↑ This picture was made by the Energy Education team.

- ↑ TPUB Engine Mechanics. (April 4, 2015). Thermal Efficiency [Online]. Available: http://enginemechanics.tpub.com/14075/css/14075_141.htm

- ↑ Hyperphysics, Carnot Cycle [Online], Available: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/thermo/carnot.html

- ↑ R. A. Hinrichs and M. Kleinbach, "Heat and Work," in Energy: Its Use and the Environment, 4th ed. Toronto, Ont. Canada: Thomson Brooks/Cole, 2006, ch.4, sec.E, pp.115